By Drew Mendoza, MD

“Jane,” a spry 72-year-old with severe aortic stenosis, came to my clinic seeking a second opinion.

At another cardiology practice, she had been worked up for progressive fatigue. She was concerned about being unable to prune her rose bushes without getting short of breath. But she had been put-off by the previous cardiologist. When they discovered

the source of her symptoms they told her, not asked her, what she was going to do. She felt pressure to proceed with more testing but didn’t fully understand her situation.

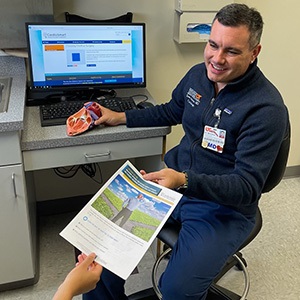

I recognized a good opportunity to use a CardioSmart decision aid.

I took my time explaining the disease process. While I answered most of Jane’s and her daughter’s questions with information they had already been told, their receptiveness was clearly different. We concluded our visit with plans to follow

up after they had had more time to review the data regarding surgery versus a percutaneous option. They also wanted to discuss their options with the rest of their family.

Challenge for FellowsUse a CardioSmart tool with 5 patients and submit an essay about your experience to your Program Director. If your narrative effectively shows Shared Decision-Making in action, you could be 1 of 3 winners.

Visit

CardioSmart.org/Challenge for more information.

Ultimately, her frailty makes her a high-risk patient for any valve replacement, but it isn’t completely prohibitive. I am hopeful that I will get to see her through her valve replacement and on the way back to her rose garden.

Stop and listen

Jane has significant comorbidities. In addition to having had a stroke due to carotid artery stenosis, she has osteoporosis, thyroiditis, and hypertension. She also fell several times this year but insisted that she had never lost consciousness during

the episodes. With this medical history, it can appear obvious to us as health care professionals that she is a poor surgical candidate.

I can see myself falling into the same trap as the other cardiologist she consulted. We all want the patient to continue living her best life possible and avoid adverse outcomes from delayed treatment. Of course she should proceed with a coronary angiogram

and cardiac CTA for pre-procedural planning for the likely percutaneous valve replacement. We cannot wait, especially as she is having pre-syncopal episodes.

But the decision aid helped me stop and listen to the patient and let her tell me how to best proceed with her care.

Improved communication

The decision aid was extremely helpful in making me pause. I stopped talking at the patient and started listening to her. But the benefit didn’t stop there. The decision aid helped my patient not only comprehend the nuances of aortic stenosis, but

also discern the right questions to ask regarding future management and the possible complications. In eastern Tennessee, health literacy is a luxury. Most patients have not had the resources or access to allow them to make well informed health decisions.

Unfortunately, we health care professionals are allowed only a brief time in the clinic to spend with patients to help them understand their disease process.

Also, the decision aid allowed me to be more efficient and thorough by covering topics I might have forgotten to discuss otherwise. In this case, the patient and her daughter were not tech-savvy, so having a printout of the decision aid was helpful. Going

forward, I will keep several paper copies of aids readily available in clinic.

Before using the decision aid, I felt pressure to cover a vast amount of information in 15-20 minutes. Now, I can spend more time getting to know my patient and their priorities when it comes to treating their disease.

In the end, I knew the decision aid would be of some benefit to my patient’s well-being; however, after utilizing it, I was most surprised to learn how much it benefitted me.

Drew Mendoza is chief cardiology fellow at Erlanger Heart and Lung Institute in Chattanooga, TN.